Вначале была сеть, и вы получили к ней доступ через браузер и все было хорошо. Материал не загружался, пока вы не нажали на что-то; вы ожидали, что куки будут отслеживать вас, и вы всегда знали, используется ли HTTPS. В общем, случайный наблюдатель имел довольно хорошее представление о том, что происходит между клиентом и сервером.

Не так в современном мире мобильных приложений. В наши дни есть огромный слой жирной абстракции поверх всего, что держит вас довольно хорошо отсоединенным от того, что на самом деле происходит. Дело в том, что это тривиальная задача, чтобы увидеть, что происходит внизу, вы просто запускаете HTTP-прокси, такой как Fiddler , бездельничаете и смотрите шоу.

Позвольте мне представить вам убогий живот iPhone, мир, где не все так, как кажется, и, конечно, не все так, как должно быть.

Там нет такого понятия, как слишком много информации — или есть?

Вот хорошее место для начала: общепринятая мудрость гласит, что эффективность сети — это всегда хорошо. Контент загружается быстрее, контент рендерится быстрее, а владельцы сайтов минимизируют свою пропускную способность. Но что еще более важно в мобильном мире, потребители часто ограничены довольно скудными ограничениями на загрузку, по крайней мере, по сегодняшним стандартам широкополосной связи. Итог: оптимизация пропускной способности в мобильных приложениях очень важна, гораздо важнее, чем в современных веб-приложениях на основе браузера.

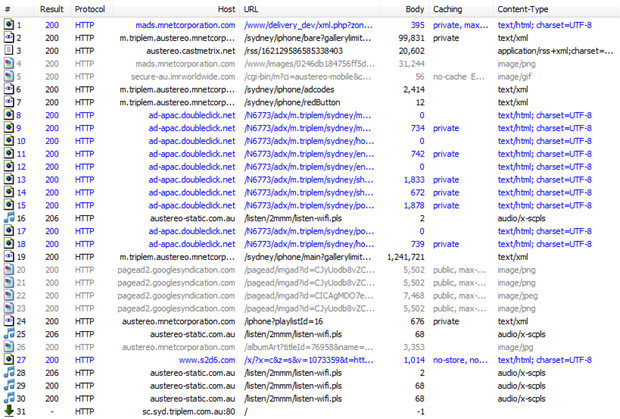

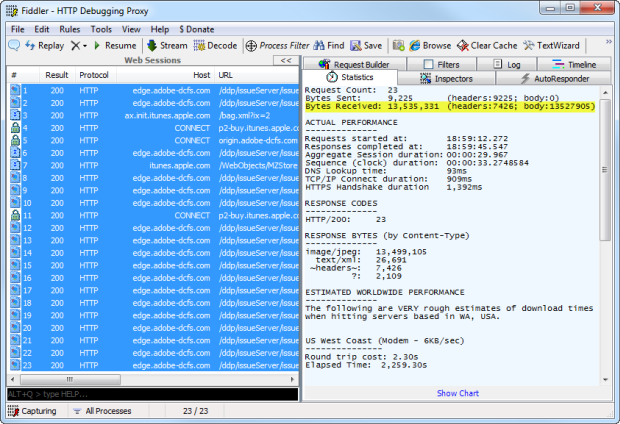

Позвольте мне привести пример того, как все это начинает работать с мобильными приложениями. Возьмите приложение Triple M , предназначенное для предоставления вам информации об одной из ведущих австралийских радиостанций, и воспроизводите ее через 3G для вас. Вот как это выглядит:

Когда все начинает идти не так, как надо, когда вы просматриваете запросы на загрузку приложения, у вас остается только 1,3 МБ:

Зачем? Ну, отчасти проблема в том, что у вас нет сжатия gzip. На самом деле, это не совсем так, некоторые мелочи сжимаются, но не большие. Пойди разберись.

Но есть также много избыточности. Например, в приведенном выше приложении вы можете увидеть первую статью под названием «Тренер Manly Sea Eagles ‘2013…», и она возвращается в запросе № 2, как и основная часть истории. Все идет нормально. Но спрыгните вниз, чтобы запросить # 19 — этот огромный 1,2 МБ — и вы получите все это снова. Ценная пропускная способность прямо из окна есть.

Теперь, конечно, это приложение предназначено для потоковой передачи аудио, поэтому оно никогда не будет ограничено пропускной способностью (как обнаружила моя жена, когда она ударила по колпачку «просто слушая радио»), и, конечно, некоторая начальная нагрузка также позволяют приложению мгновенно реагировать, когда вы переходите к истории. Но приведенные выше шаблоны просто не нужны; зачем отправлять избыточные данные в несжатом формате?

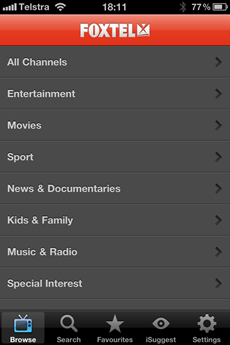

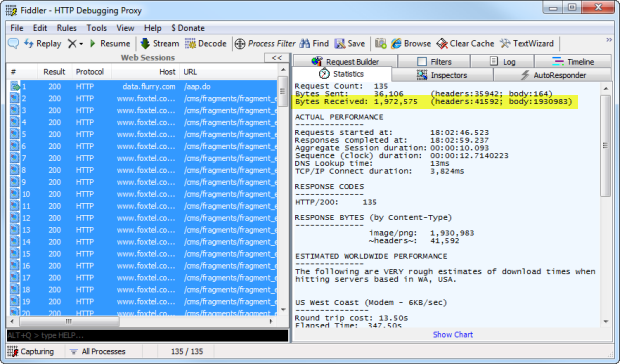

Вот грязный секрет Фокстела; Как вы думаете, сколько вам потребуется пропускной способности, чтобы загрузить приложение, которое вы видите ниже? Несколько кб? Может быть, сто КБ, чтобы получить хороший сжатый канал JSON со всеми каналами? Может быть, ничего, потому что это будет тянуть данные по требованию, когда вы на самом деле что-то делаете ?

Думаю, вам еще понадобится пара мег, чтобы запустить приложение:

Часть проблемы показана под заголовком Content-Type выше; это почти все файлы PNG. На самом деле, это 134 PNG-файла. Зачем? Я имею в виду, что может оправдать почти 2 мегапикселя PNG только для того, чтобы открыть приложение? Посмотрите на этого парня:

Это только одно из реальных изображений в оригинальном размере. И зачем нужен этот огромный PNG? Чтобы создать этот экран:

Хм, на самом деле не вариант использования для PNG размером 425×243, 86 КБ. Зачем? Возможно, потому что, как мы видели ранее , разработчики любят брать что-то, что уже существует, и переназначать его вне его предназначенного контекста, и, как и в вышеупомянутой ссылке, это может начать вызывать всевозможные проблемы. К сожалению, это создает неприятные ощущения для пользователя, так как вы сидите и ждете, пока что-то загрузится, а это неприятно для вашего (возможно, скудного) распределения данных.

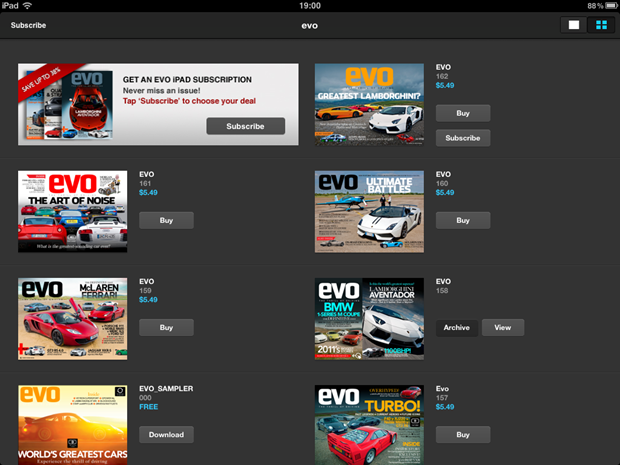

Но мы только разогреваемся. Давайте посмотрим на превосходный, визуально ошеломляющий журнал EVO на iPad. Начальный экран — это просто список изданий, например:

Давайте немного поговорим в реальном выражении; разрешение iPad — 1024×768 или то, что мы привыкли считать «высоким разрешением» не так давно. Изображение выше было уменьшено примерно до 60% от оригинала, но на iPad каждая из этих маленьких обложек журналов изначально была размером 180×135, которая даже сохранена в формате PNG высокого качества, и может быть значительно дешевле 50 КБ за штуку. Однако:

Тринадцать с половиной мег? Куда делась земля? Вот подсказка:

Давай, нажми, я подожду.

Да, 1,6 МБ.

Ширина 4267 пикселей, высота 3200 пикселей.

Why? I have no idea, perhaps the art department just sent over the originals intended for print and it was “easy” to dump that into the app. All you can do in the app without purchasing the magazine (for which you expect a big bandwidth hit), is just look at those thumbnails. So there you go, 13.5MB chewed out of your 3G plan before you even do anything just because images are being loaded with 560 times more pixels than they need.

The secret stalker within

Apps you install directly onto the OS have always been a bit of a black box. I mean it’s not the same “view source” world that we’ve become so accustomed to with the web over the last decade and a half where it’s pretty easy to see what’s going on under the covers (at least under the browser covers). With the volume and affordability of iOS apps out there, we’re now well and truly back in the world of rich clients which performs all sorts of things out of your immediate view, and some of them are rather interesting.

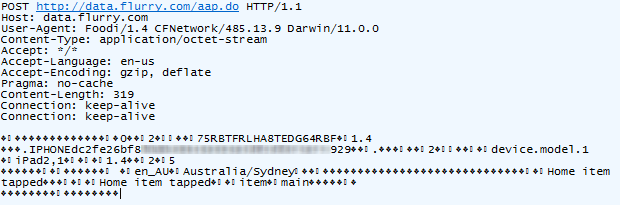

Let’s take cooking as an example; the ABC Foodi app is a beautiful piece of work. I mean it really is visually delightful and a great example of what can be done on the iPad:

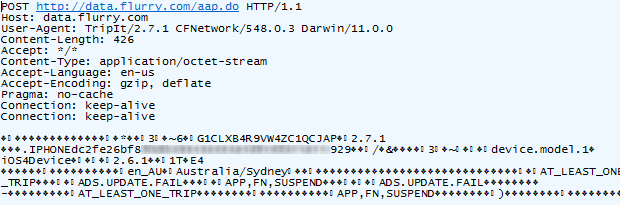

But it’s spying on you and phoning home at every opportunity. For example, you can’t just open the app and start browsing around in the privacy of your own home, oh no, this activity is immediately reported (I’m deliberately obfuscating part of the device ID):

Ok, that’s a mostly innocuous, but it looks like my location – or at least my city – is also in there so obviously my movements are traceable. Sure, far greater location fidelity can usually be derived from the IP address anyway (and they may well be doing this on the back end), but it’s interesting to see this explicitly captured.

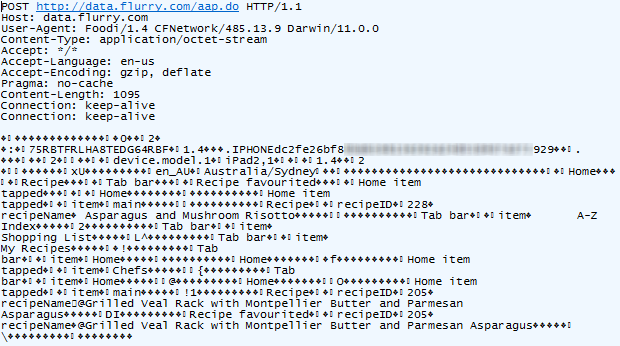

Let’s try something else, say, favouriting a dish:

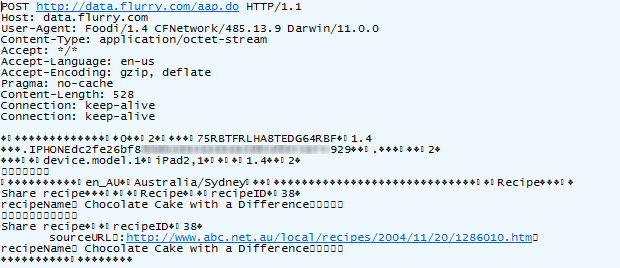

Not the asparagus!!! Looks like you can’t even create a favourite without your every move being tracked. But it’s actually even more than that; I just located a nice chocolate cake and emailed it to myself using the “share” feature. Here’s what happened next:

The app tracks your every move and sends it back to base in small batches. In this case, that base is at flurry.com, and who are these guys? Well it’s quite clear from their website:

Flurry powers acquisition, engagement and monetization for the new mobile app economy, using powerful data and applying game-changing insight.

Funny, I knew I’d seen that somewhere before!

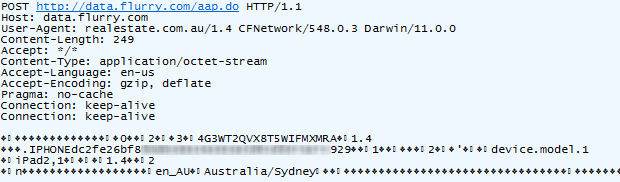

Here’s something I’ve seen before: POST requests to data.flurry.com. It’s perfectly obvious when you use the realestate.com.au iPad app:

Uh, except it isn’t really obvious, it’s another sneaky backdoor to help power acquisitions and monetise the new app economy with game-changing insight. Here’s what it’s doing and clearly it has nothing to do with finding real estate:

Hang on – does that partially obfuscated device ID look a bit familiar?! Yes it does, so Flurry now knows both what I’m cooking and which kitchen I’d like to be cooking it in. And in case you missed it, the first request when the Foxtel app was loaded earlier on was also to data.flurry.com. Oh, and how about those travel plans with TripIt – the cheerful blue sky looks innocuous enough:

But under the covers:

Suddenly monetisation with powerful data starts to make more sense.

But this is no different to a tracking cookie on a website, right? Well, yes and no. Firstly, tracking cookies can be disabled. If you don’t like ‘em, turn ‘em off. Not so the iOS app as everything is hidden under the covers. Actually, it’s in much the same way as a classic app that gets installed on any OS although in the desktop world, we’ve become accustomed to being asked if we’re happy to share our activities “for product improvement purposes”.

These privacy issues simply come down to this: what does the user expect? Do they expect to be tracked when browsing a cook book installed on their local device? And do they expect this activity to be cross-referenceable with the use of other apparently unrelated apps? I highly doubt it, and therein lays the problem.

Security? We don’t need no stinkin’ security!

Many people are touting mobile apps as the new security frontier, and rightly so IMHO. When I wrote about Westfield last month I observed how easy it was for the security of services used by apps to be all but ignored as they don’t have the same direct public exposure as the apps themselves. A browse through my iPhone collection supports the theory that mobile app security is taking a back seat to their browser-based peers.

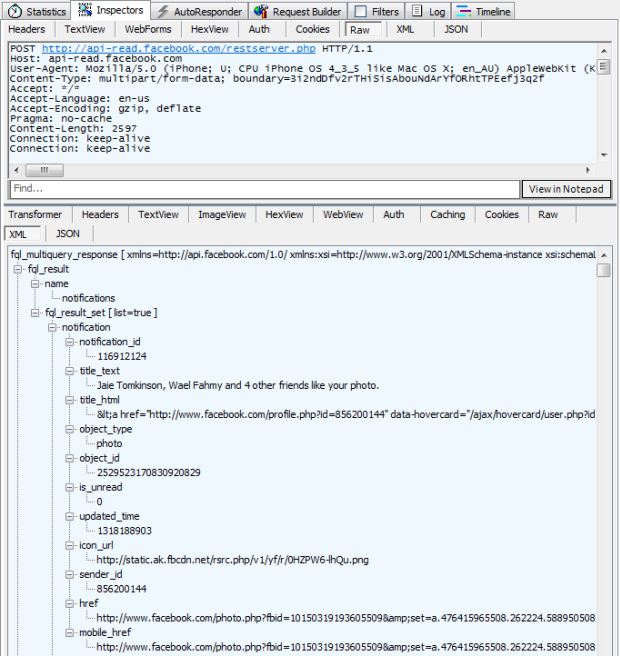

Let’s take the Facebook app. Now to be honest, this one surprised me a little. Back in Jan of this year, Facebook allowed opt-in SSL or in or in the words of The Register, this is also known as “Turn it on yourself…bitch”. Harsh, but fair – this valuable security feature was going to be overlooked by many, many people. “SS what?”

Unfortunately, the very security that is offered to browser-based Facebook users is not accessible on the iPhone client. You know, the device which is most likely to be carried around to wireless hotspots where insecure communications are most vulnerable. Here’s what we’re left with:

This is especially surprising as that little bit of packet-sniffing magic that is Firesheep was no doubt the impetus for even having the choice of enable SSL. But here we are, one year on and apparently Facebook is none the wiser.

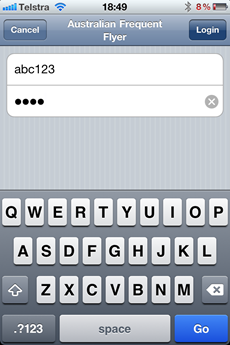

Let’s change pace a little and take a look inside the Australian Frequent Flyer app. This is “Australia’s leading Frequent Flyer Community” and clearly a community of such standing would take security very, very seriously. Let’s login:

As with the Qantas example above, you have absolutely no idea how these credentials are being transported across the wire. Well, unless you have Fiddler then it’s perfectly clear they’re just being posted to this HTTP address: http://www.australianfrequentflyer.com.au/mobiquo-withsponsor/mobiquo.php

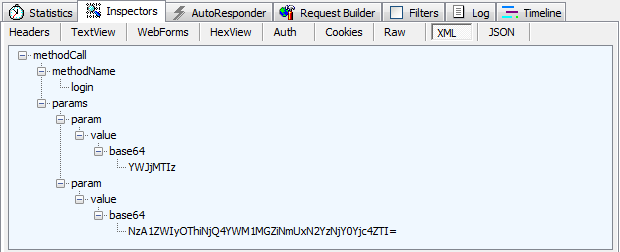

And of course it’s all very simple to see the post body which in this case, is little chunk of XML:

Bugger, clearly this is going to tack some sort of hacker mastermind to figure out what these credentials are! Except it doesn’t, it just takes a bit of Googling. There are two parameters and they’re both Base64 encoded. How do we know this? Well, firstly it tells us in one of the XML nodes and secondly, it’s a pretty common practice to encode data in this fashion before shipping it around the place (refer the link in this paragraph for the ins and outs of why this is useful).

So we have a value of “YWJjMTIz” and because Base64 is designed to allow for simple encoding and decoding (unlike a hash which is a one way process), you can simply convert this back to plain text using any old Base64 decoder. Here’s an online one right here and it tells us this value is “abc123”. Well how about that!

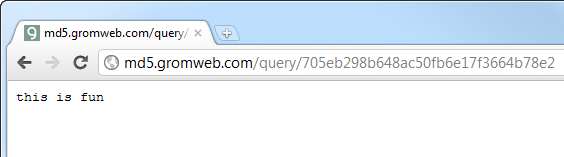

The next value is “NzA1ZWIyOThiNjQ4YWM1MGZiNmUxN2YzNjY0Yjc4ZTI=” which is obviously going to be the password. Once we Base64 decode this, we have something a little different: “705eb298b648ac50fb6e17f3664b78e2?”. Wow, that’s an impressive password! Except that as we well know, people choosing impressive passwords is a very rare occurrence indeed so in all likelihood this is a hash. Now there are all sorts of nifty brute forcing tools out there but when it comes to finding the plain text of a hash, nothing beats Google. And what does the first result Google gives us? Take a look:

I told you that was a useless password dammit! You see the thing is, there’s a smorgasbord of hashes and their plain text equivalents just sitting out there waiting to be searched which is why it’s always important to apply a cryptographically random salt to the plain text before hashing. A straight hash of most user-created passwords – which we know are generally crap – can very frequently be resolved to plain text in about 5 seconds via Google.

The bottom line is that this is almost no better than plain text credentials and it’s definitely no alternative to transport layer security. I’ve had numerous conversations with developers before trying to explain the difference between encoding, hashing and encryption and if I were to take a guess, someone behind this thinks they’re “encrypted” the password. Not quite.

But is this really any different to logging onto the Australian Frequent Flyer website which also (sadly) has no HTTPS? Yes, what’s different is that firstly, on the website it’s clear to see that no HTTPS has been employed, or at least not properly employed (the login form isn’t loaded over HTTPS). I can then make a judgement call on the trust and credibility of the site; I can’t do that with the app. But secondly, this is a mobile app – a mobile travel app – you know, the kind of thing that’s going to be used while roaming around wireless hotspots vulnerable to eavesdropping. It’s more important than ever to protect sensitive communications and the app totally misses the mark on that one.

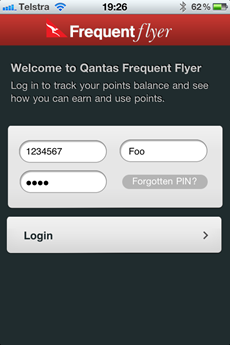

While we’re talking travel apps, let’s take another look at Qantas. I’ve written about these guys before, in fact they made my Who’s who of bad password practices list earlier in the year. Although they made a small attempt at implementing security by posting to SSL, as I’ve said before, SSL is not about encryption and loading login forms over HTTP is a big no-no. But at least they made some attempt.

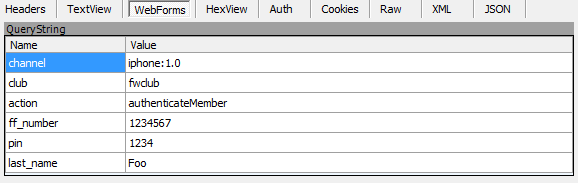

So why does the iPhone app just abandon all hope and do everything without any transport layer encryption at all? Even worse, it just whacks all the credentials in a query string. So it’s a GET request. Over HTTP. Here’s how it goes down:

This is a fairly typical login screen. So far, so good, although of course there’s no way to know how the credentials are handled. At least, that is, until you take a look at the underlying request that’s made. Here’s those query string parameters:

Or put simply, it’s just a request to this URL: http://wsl.qantas.com.au/qffservices/?channel=iphone:1.0&club=fwclub&action=authenticateMember&ff_number=1234567&pin=1234&last_name=Foo

Go ahead, give it a run. What I find most odd about this situation is that clearly a conscious decision was made to apply some degree of transport encryption to the browser app, why not the mobile app? Why must the mobile client remain the poor cousin when it comes to basic security measures? It’s not it’s going to be used inside any highly vulnerable public wifi hotspots like, oh I don’t know, an airport lounge, right?

Apps continue to get security wrong. Not just iOS apps mind you, there are plenty of problems on Android and once anyone buys a Windows Mobile 7 device we’ll see plenty of problems on those too. It’s just too easy to get wrong and when you do get it wrong, it’s further out of sight than your traditional web app. Fortunately the good folks at OWASP are doing some great work around a set of Top 10 mobile security risks so there’s certainly acknowledge of the issues and work being done to help developers get mobile security right.

Summary

What I discovered about is the result of casually observing some of only a few dozen apps I have installed on my iOS devices. There are about half a million more out there and if I were a betting man, my money would be the issues above only being the tip of the iceberg.

You can kind of get how these issues happen; every man and his dog appears to be building mobile apps these days and a low bar to entry is always going to introduce some quality issues. But Facebook? And Qantas? What are their excuses for making security take a back seat?

Developers can get away with more sloppy or sneaky practices in mobile apps as the execution is usually further out of view.

You can smack the user with a massive asynchronous download as their attention is on other content; but it kills their data plan.

You can track their moves across entirely autonomous apps; but it erodes their privacy.

And most importantly to me, you can jeopardise their security without their noticing; but the potential ramifications are severe.

We live in interesting times.

Source: http://www.troyhunt.com/2011/10/secret-ios-business-what-you-dont-know.html