PL / SQL — одна из таких вещей.

Большинство людей стараются держаться подальше от этого. Мало кто действительно любит это. У меня просто случился Стокгольмский синдром, так как я много работаю с банками.

Даже если синтаксис PL / SQL и инструментарий иногда напоминают мне о старых добрых временах…

«Фицджеральд, мы едем за синяками». Я перемотаю ленту. — «Нет коровы, Лоуренс. Мы можем вставить новый картридж PL / SQL в любое время ».

Изображение в свободном доступе

… Я все еще считаю, что процедурный язык (ну, любой язык) в сочетании с SQL может творить чудеса с точки зрения производительности, производительности и выразительности.

В этой статье мы увидим позже, как мы можем добиться того же с SQL (и PL / SQL) в Java, используя jOOQ .

Но сначала немного истории…

Доступ к PL / SQL из Java

Одна из главных причин, почему разработчики Java, в частности, воздерживаются от написания своего собственного кода PL / SQL, заключается в том, что интерфейс между PL / SQL и Java — ojdbc — является серьезной проблемой. В следующих примерах мы увидим, как это происходит.

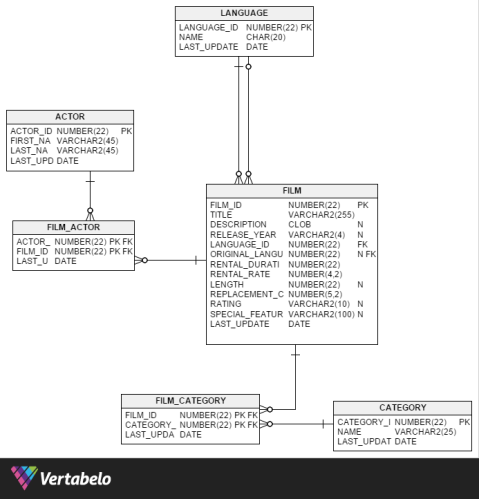

Предположим, мы работаем над портом Oracle популярной базы данных Sakila ( изначально созданной для MySQL ). Этот конкретный порт Sakila / Oracle был реализован DB Software Laboratory и опубликован под лицензией BSD.

Вот частичное представление этой базы данных Sakila.

ERD создан с помощью vertabelo.com — узнайте, как использовать Vertabelo с jOOQ

Теперь, давайте предположим, что у нас есть API в базе данных, который не предоставляет вышеуказанную схему, но вместо этого предоставляет API PL / SQL . API может выглядеть примерно так:

CREATE TYPE LANGUAGE_T AS OBJECT ( language_id SMALLINT, name CHAR(20), last_update DATE ); / CREATE TYPE LANGUAGES_T AS TABLE OF LANGUAGE_T; / CREATE TYPE FILM_T AS OBJECT ( film_id int, title VARCHAR(255), description CLOB, release_year VARCHAR(4), language LANGUAGE_T, original_language LANGUAGE_T, rental_duration SMALLINT, rental_rate DECIMAL(4,2), length SMALLINT, replacement_cost DECIMAL(5,2), rating VARCHAR(10), special_features VARCHAR(100), last_update DATE ); / CREATE TYPE FILMS_T AS TABLE OF FILM_T; / CREATE TYPE ACTOR_T AS OBJECT ( actor_id numeric, first_name VARCHAR(45), last_name VARCHAR(45), last_update DATE ); / CREATE TYPE ACTORS_T AS TABLE OF ACTOR_T; / CREATE TYPE CATEGORY_T AS OBJECT ( category_id SMALLINT, name VARCHAR(25), last_update DATE ); / CREATE TYPE CATEGORIES_T AS TABLE OF CATEGORY_T; / CREATE TYPE FILM_INFO_T AS OBJECT ( film FILM_T, actors ACTORS_T, categories CATEGORIES_T ); /

You’ll notice immediately, that this is essentially just a 1:1 copy of the schema in this case modelled as Oracle SQL OBJECT and TABLE types, apart from the FILM_INFO_T type, which acts as an aggregate.

Now, our DBA (or our database developer) has implemented the following API for us to access the above information:

CREATE OR REPLACE PACKAGE RENTALS AS FUNCTION GET_ACTOR(p_actor_id INT) RETURN ACTOR_T; FUNCTION GET_ACTORS RETURN ACTORS_T; FUNCTION GET_FILM(p_film_id INT) RETURN FILM_T; FUNCTION GET_FILMS RETURN FILMS_T; FUNCTION GET_FILM_INFO(p_film_id INT) RETURN FILM_INFO_T; FUNCTION GET_FILM_INFO(p_film FILM_T) RETURN FILM_INFO_T; END RENTALS; /

This, ladies and gentlemen, is how you can now…

… tediously access the PL/SQL API with JDBC

So, in order to avoid the awkward CallableStatement with its OUT parameter registration and JDBC escape syntax, we’re going to fetch a FILM_INFO_T record via a SQL statement like this:

try(PreparedStatement stmt = conn.prepareStatement(

"SELECT rentals.get_film_info(1) FROM DUAL");

ResultSet rs = stmt.executeQuery()) {

// STRUCT unnesting here...

}

So far so good. Luckily, there is Java 7’s try-with-resources to help us clean up those myriad JDBC objects. Now how to proceed? What will we get back from this ResultSet? A java.sql.Struct:

while(rs.next()) {

Struct film_info_t = (Struct) rs.getObject(1);

// And so on...

}

Now, the brave ones among you would continue downcasting the java.sql.Struct to an even more obscure and arcane oracle.sql.STRUCT, which contains almost no Javadoc, but tons of deprecated additional, vendor-specific methods.

For now, let’s stick with the “standard API”, though.

Interlude:

Let’s take a moment to appreciate JDBC in times of Java 8.

When Java 5 was introduced, so were generics. We have rewritten our big code bases to remove all sorts of meaningless boilerplate type casts that are now no longer needed. With the exception of JDBC. When it comes to JDBC, guessing appropriate types is all a matter of luck. We’re accessing complex nested data structures provided by external systems by dereferencing elements by index, and then taking wild guesses at the resulting data types.

Lambdas have just been introduced, yet JDBC still talks to the mainframe.

Rhonda said, she put that STRUCT right between jack 73 and 75 on array F-B4. I wonder if I need my AC/DC converter to plug it

Image in public domain

And then…

And here be dragons. And STRUCTS

Original image in public domain

OK, enough of these rants.

Let’s continue navigating our STRUCT

while(rs.next()) {

Struct film_info_t = (Struct) rs.getObject(1);

Struct film_t = (Struct) film_info_t.getAttributes()[0];

String title = (String) film_t.getAttributes()[1];

Clob description_clob = (Clob) film_t.getAttributes()[2];

String description = description_clob.getSubString(1, (int) description_clob.length());

Struct language_t = (Struct) film_t.getAttributes()[4];

String language = (String) language_t.getAttributes()[1];

System.out.println("Film : "+ title);

System.out.println("Description: "+ description);

System.out.println("Language : "+ language);

}

From the initial STRUCT that we received at position 1 from the ResultSet, we can continue dereferencing attributes by index. Unfortunately, we’ll constantly need to look up the SQL type in Oracle (or in some documentation) to remember the order of the attributes:

CREATE TYPE FILM_INFO_T AS OBJECT ( film FILM_T, actors ACTORS_T, categories CATEGORIES_T ); /

And that’s not it! The first attribute of type FILM_T is yet another, nested STRUCT. And then, those horrible CLOBs. The above code is not strictly complete. In some cases that only the maintainers of JDBC can fathom, java.sql.Clob.free() has to be called to be sure that resources are freed in time. Remember that CLOB, depending on your database and driver configuration, may live outside the scope of your transaction.

Unfortunately, the method is called free() instead of AutoCloseable.close(), such that try-with-resources cannot be used. So here we go:

List<Clob> clobs = newArrayList<>();

while(rs.next()) {

try{

Struct film_info_t = (Struct) rs.getObject(1);

Struct film_t = (Struct) film_info_t.getAttributes()[0];

String title = (String) film_t.getAttributes()[1];

Clob description_clob = (Clob) film_t.getAttributes()[2];

String description = description_clob.getSubString(1, (int) description_clob.length());

Struct language_t = (Struct) film_t.getAttributes()[4];

String language = (String) language_t.getAttributes()[1];

System.out.println("Film : "+ title);

System.out.println("Description: "+ description);

System.out.println("Language : "+ language);

}

finally{

// And don't think you can call this early, either

// The internal specifics are mysterious!

for(Clob clob : clobs)

clob.free();

}

}

That’s about it. Now we have found ourselves with some nice little output on the console:

Film : ACADEMY DINOSAUR

Description: A Epic Drama of a Feminist And a Mad

Scientist who must Battle a Teacher in

The Canadian Rockies

Language : English

That’s about it – You may think! But…

The pain has only started

… because we’re not done yet. There are also two nested table types that we need to deserialise from the STRUCT. If you haven’t given up yet (bear with me, good news is nigh), you’ll enjoy reading about how to fetch and unwind a java.sql.Array. Let’s continue right after the printing of the film:

Array actors_t = (Array) film_info_t.getAttributes()[1]; Array categories_t = (Array) film_info_t.getAttributes()[2];

Again, we’re accessing attributes by indexes, which we have to remember, and which can easily break. The ACTORS_T array is nothing but yet another wrapped STRUCT:

System.out.println("Actors : ");

Object[] actors = (Object[]) actors_t.getArray();

for(Object actor : actors) {

Struct actor_t = (Struct) actor;

System.out.println(

" "+ actor_t.getAttributes()[1]

+ " "+ actor_t.getAttributes()[2]);

}

You’ll notice a few things:

- The

Array.getArray()method returns an array. But it declares returningObject. We have to manually cast. - We can’t cast to

Struct[]even if that would be a sensible type. But the type returned by ojdbc isObject[](containingStructelements) - The foreach loop also cannot dereference a

Structfrom the right hand side. There’s no way of coercing the type ofactorinto what we know it really is - We could’ve used Java 8 and Streams and such, but unfortunately, all lambda expressions that can be passed to the Streams API disallow throwing of checked exceptions. And JDBC throws checked exceptions. That’ll be even uglier.

Anyway. Now that we’ve finally achieved this, we can see the print output:

Film : ACADEMY DINOSAUR

Description: A Epic Drama of a Feminist And a Mad

Scientist who must Battle a Teacher in

The Canadian Rockies

Language : English

Actors :

PENELOPE GUINESS

CHRISTIAN GABLE

LUCILLE TRACY

SANDRA PECK

JOHNNY CAGE

MENA TEMPLE

WARREN NOLTE

OPRAH KILMER

ROCK DUKAKIS

MARY KEITEL

When will this madness stop?

It’ll stop right here!

So far, this article read like a tutorial (or rather: medieval torture) of how to deserialise nested user-defined types from Oracle SQL to Java (don’t get me started on serialising them again!)

In the next section, we’ll see how the exact same business logic (listing Film with ID=1 and its actors) can be implemented with no pain at all using jOOQ and its source code generator. Check this out:

// Simply call the packaged stored function from

// Java, and get a deserialised, type safe record

FilmInfoTRecord film_info_t = Rentals.getFilmInfo1(

configuration, newBigInteger("1"));

// The generated record has getters (and setters)

// for type safe navigation of nested structures

FilmTRecord film_t = film_info_t.getFilm();

// In fact, all these types have generated getters:

System.out.println("Film : "+ film_t.getTitle());

System.out.println("Description: "+ film_t.getDescription());

System.out.println("Language : "+ film_t.getLanguage().getName());

// Simply loop nested type safe array structures

System.out.println("Actors : ");

for(ActorTRecord actor_t : film_info_t.getActors()) {

System.out.println(

" "+ actor_t.getFirstName()

+ " "+ actor_t.getLastName());

}

System.out.println("Categories : ");

for(CategoryTRecord category_t : film_info_t.getCategories()) {

System.out.println(category_t.getName());

}

Is that it?

Yes!

Wow, I mean, this is just as though all those PL/SQL types and procedures / functions were actually part of Java. All the caveats that we’ve seen before are hidden behind those generated types and implemented in jOOQ, so you can concentrate on what you originally wanted to do. Access the data objects and do meaningful work with them. Not serialise / deserialise them!

Let’s take a moment and appreciate this consumer advertising:

Not convinced yet?

I told you not to get me started on serialising the types to JDBC. And I won’t, but here’s how to serialise the types to jOOQ, because that’s a piece of cake!

Let’s consider this other aggregate type, that returns a customer’s rental history:

CREATE TYPE CUSTOMER_RENTAL_HISTORY_T AS OBJECT ( customer CUSTOMER_T, films FILMS_T ); /

And the full PL/SQL package specs:

CREATE OR REPLACE PACKAGE RENTALS AS FUNCTION GET_ACTOR(p_actor_id INT) RETURN ACTOR_T; FUNCTION GET_ACTORS RETURN ACTORS_T; FUNCTION GET_CUSTOMER(p_customer_id INT) RETURN CUSTOMER_T; FUNCTION GET_CUSTOMERS RETURN CUSTOMERS_T; FUNCTION GET_FILM(p_film_id INT) RETURN FILM_T; FUNCTION GET_FILMS RETURN FILMS_T; FUNCTION GET_CUSTOMER_RENTAL_HISTORY(p_customer_id INT) RETURN CUSTOMER_RENTAL_HISTORY_T; FUNCTION GET_CUSTOMER_RENTAL_HISTORY(p_customer CUSTOMER_T) RETURN CUSTOMER_RENTAL_HISTORY_T; FUNCTION GET_FILM_INFO(p_film_id INT) RETURN FILM_INFO_T; FUNCTION GET_FILM_INFO(p_film FILM_T) RETURN FILM_INFO_T; ENDRENTALS; /

So, when calling RENTALS.GET_CUSTOMER_RENTAL_HISTORY we can find all the films that a customer has ever rented. Let’s do that for all customers whose FIRST_NAME is “JAMIE”, and this time, we’re using Java 8:

// We call the stored function directly inline in

// a SQL statement

dsl().select(Rentals.getCustomer(

CUSTOMER.CUSTOMER_ID

))

.from(CUSTOMER)

.where(CUSTOMER.FIRST_NAME.eq("JAMIE"))

// This returns Result<Record1<CustomerTRecord>>

// We unwrap the CustomerTRecord and consume

// the result with a lambda expression

.fetch()

.map(Record1::value1)

.forEach(customer -> {

System.out.println("Customer : ");

System.out.println("- Name : "

+ customer.getFirstName()

+ " "+ customer.getLastName());

System.out.println("- E-Mail : "

+ customer.getEmail());

System.out.println("- Address : "

+ customer.getAddress().getAddress());

System.out.println(" "

+ customer.getAddress().getPostalCode()

+ " "+ customer.getAddress().getCity().getCity());

System.out.println(" "

+ customer.getAddress().getCity().getCountry().getCountry());

// Now, lets send the customer over the wire again to

// call that other stored procedure, fetching his

// rental history:

CustomerRentalHistoryTRecord history =

Rentals.getCustomerRentalHistory2(dsl().configuration(), customer);

System.out.println(" Customer Rental History : ");

System.out.println(" Films : ");

history.getFilms().forEach(film -> {

System.out.println(" Film : "

+ film.getTitle());

System.out.println(" Language : "

+ film.getLanguage().getName());

System.out.println(" Description : "

+ film.getDescription());

// And then, let's call again the first procedure

// in order to get a film's actors and categories

FilmInfoTRecord info =

Rentals.getFilmInfo2(dsl().configuration(), film);

info.getActors().forEach(actor -> {

System.out.println(" Actor : "

+ actor.getFirstName() + " "+ actor.getLastName());

});

info.getCategories().forEach(category -> {

System.out.println(" Category : "

+ category.getName());

});

});

});

… and a short extract of the output produced by the above:

Customer :

- Name : JAMIE RICE

- E-Mail : JAMIE.RICE@sakilacustomer.org

- Address : 879 Newcastle Way

90732 Sterling Heights

United States

Customer Rental History :

Films :

Film : ALASKA PHANTOM

Language : English

Description : A Fanciful Saga of a Hunter

And a Pastry Chef who must

Vanquish a Boy in Australia

Actor : VAL BOLGER

Actor : BURT POSEY

Actor : SIDNEY CROWE

Actor : SYLVESTER DERN

Actor : ALBERT JOHANSSON

Actor : GENE MCKELLEN

Actor : JEFF SILVERSTONE

Category : Music

Film : ALONE TRIP

Language : English

Description : A Fast-Paced Character

Study of a Composer And a

Dog who must Outgun a Boat

in An Abandoned Fun House

Actor : ED CHASE

Actor : KARL BERRY

Actor : UMA WOOD

Actor : WOODY JOLIE

Actor : SPENCER DEPP

Actor : CHRIS DEPP

Actor : LAURENCE BULLOCK

Actor : RENEE BALL

Category : Music

If you’re using Java and PL/SQL…

… then you should click on the below banner and download the free trial right now to experiment with jOOQ and Oracle:

The Oracle port of the Sakila database is available from this URL for free, under the terms of the BSD license:

https://github.com/jOOQ/jOOQ/tree/master/jOOQ-examples/Sakila/oracle-sakila-db

Finally, it is time to enjoy writing PL/SQL again!