[Эта статья была написана Eqbal Quran — инженер-программист @ Toptal ]

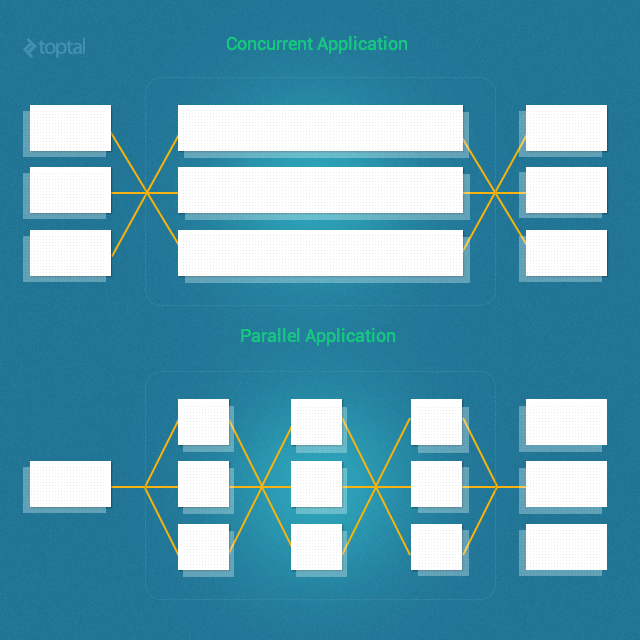

Давайте начнем с того, что проясним слишком распространенную путаницу; а именно: параллелизм и параллелизм не одно и то же (т. е. параллелизм! = параллель).

В частности, параллелизм — это когда две задачи могут запускаться, выполняться и завершаться в перекрывающиеся периоды времени. Однако это не обязательно означает, что они когда-либо будут работать одновременно (например, несколько потоков на одноядерном компьютере). Напротив, параллелизм — это когда две задачи выполняются буквально одновременно (например, несколько потоков на многоядерном процессоре).

Ключевым моментом здесь является то, что параллельные процессы и / или потоки не обязательно будут работать параллельно.

Эта статья содержит практическое (а не теоретическое) описание различных методов и подходов, доступных для параллелизма и параллелизма в Ruby.

Наш тестовый кейс

Для простого тестового примера я создам Mailerкласс и добавлю функцию Фибоначчи (а не sleep()метод), чтобы сделать каждый запрос более ресурсоемким, как показано ниже:

class Mailer

def self.deliver(&block)

mail = MailBuilder.new(&block).mail

mail.send_mail

end

Mail = Struct.new(:from, :to, :subject, :body) do

def send_mail

fib(30)

puts "Email from: #{from}"

puts "Email to : #{to}"

puts "Subject : #{subject}"

puts "Body : #{body}"

end

def fib(n)

n < 2 ? n : fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

end

end

class MailBuilder

def initialize(&block)

@mail = Mail.new

instance_eval(&block)

end

attr_reader :mail

%w(from to subject body).each do |m|

define_method(m) do |val|

@mail.send("#{m}=", val)

end

end

end

end

Затем мы можем вызвать этот Mailerкласс следующим образом для отправки почты:

Mailer.deliver do from "eki@eqbalq.com" to "jill@example.com" subject "Threading and Forking" body "Some content" end

(Примечание. Исходный код этого тестового примера доступен здесь, на github.)

Чтобы установить базовый уровень для сравнения, давайте начнем с простого теста, 100 раз вызывающего почтовую программу:

puts Benchmark.measure{

100.times do |i|

Mailer.deliver do

from "eki_#{i}@eqbalq.com"

to "jill_#{i}@example.com"

subject "Threading and Forking (#{i})"

body "Some content"

end

end

}

Это дало следующие результаты на четырехъядерном процессоре с MRI Ruby 2.0.0p353:

15.250000 0.020000 15.270000 ( 15.304447)

Несколько процессов против нескольких потоков

Не существует ответа «один размер подходит всем», когда речь заходит о решении, использовать ли несколько процессов или многопоточность вашего приложения. В таблице ниже приведены некоторые ключевые факторы, которые необходимо учитывать.

| Процессы | Потоки |

|---|---|

| Использует больше памяти | Использует меньше памяти |

| Если родитель умирает до того, как уйдут дети, дети могут стать зомби-процессами. | Все потоки умирают, когда процесс умирает (без шансов зомби) |

| Более дорого для разветвленных процессов переключать контекст, так как ОС должна сохранять и перезагружать все | У потоков значительно меньше накладных расходов, поскольку они совместно используют адресное пространство и память |

| Разветвленным процессам предоставляется новое пространство виртуальной памяти (изоляция процессов) | Потоки совместно используют одну и ту же память, поэтому необходимо контролировать и решать параллельные проблемы с памятью |

| Требуется межпроцессное взаимодействие | Может «общаться» через очереди и разделяемую память |

| Медленнее создавать и уничтожать | Быстрее создавать и уничтожать |

| Проще кодировать и отлаживать | Может быть значительно сложнее для кодирования и отладки |

Примеры решений Ruby, которые используют несколько процессов:

- Resque : библиотека Ruby с поддержкой Redis для создания фоновых заданий, размещения их в нескольких очередях и последующей их обработки.

- Unicorn : HTTP-сервер для приложений Rack, предназначенный для обслуживания быстрых клиентов только в соединениях с малой задержкой и высокой пропускной способностью и использования возможностей ядер Unix / Unix-подобных.

Примеры решений Ruby, использующих многопоточность:

- Sidekiq : полнофункциональная среда фоновой обработки для Ruby. Его целью является простота интеграции с любым современным приложением Rails и значительно более высокая производительность, чем у других существующих решений.

- Puma : веб-сервер Ruby, созданный для параллелизма.

- Тонкий : очень быстрый и простой веб-сервер Ruby.

Несколько процессов

Прежде чем мы рассмотрим варианты многопоточности, давайте рассмотрим более простой путь порождения нескольких процессов.

В Ruby fork()системный вызов используется для создания «копии» текущего процесса. Этот новый процесс запланирован на уровне операционной системы, поэтому он может выполняться одновременно с исходным процессом, как и любой другой независимый процесс. ( Примечание: fork() это системный вызов POSIX, поэтому он недоступен, если вы используете Ruby на платформе Windows.)

Итак, давайте запустим наш тестовый пример, но на этот раз используем fork()несколько процессов:

puts Benchmark.measure{

100.times do |i|

fork do

Mailer.deliver do

from "eki_#{i}@eqbalq.com"

to "jill_#{i}@example.com"

subject "Threading and Forking (#{i})"

body "Some content"

end

end

end

Process.waitall

}

( Process.waitallожидает завершения всех дочерних процессов и возвращает массив статусов процессов.)

Этот код теперь дает следующие результаты (опять же, на четырехъядерном процессоре с MRI Ruby 2.0.0p353):

0.000000 0.030000 27.000000 ( 3.788106)

Не слишком потрепанный! Мы сделали почтовую программу примерно в 5 раз быстрее, просто изменив пару строк кода (т.е. используя fork()).

Не волнуйтесь, хотя. Хотя он может пытаться использовать разветвление, так как это простое решение для параллелизма, у него есть главный недостаток — объем памяти, который он будет использовать. Форкинг довольно дорог, особенно если копируемый при записи (CoW) не используется интерпретатором Ruby, который вы используете. Например, если ваше приложение использует 20 МБ памяти, разветвление 100 раз может потребовать до 2 ГБ памяти!

Кроме того, хотя многопоточность также имеет свои собственные сложности, существует ряд сложностей, которые необходимо учитывать при использовании fork(), таких как дескрипторы общих файлов и семафоры (между родительскими и дочерними разветвленными процессами), необходимость взаимодействия через каналы и т. Д. на.

Многопоточность

Хорошо, теперь давайте попробуем сделать ту же программу быстрее, используя вместо этого методы многопоточности.

Несколько потоков в одном процессе имеют значительно меньше накладных расходов, чем соответствующее количество процессов, поскольку они совместно используют адресное пространство и память.

Имея это в виду, давайте вернемся к нашему тестовому примеру, но на этот раз с использованием Threadкласса Ruby :

threads = []

puts Benchmark.measure{

100.times do |i|

threads << Thread.new do

Mailer.deliver do

from "eki_#{i}@eqbalq.com"

to "jill_#{i}@example.com"

subject "Threading and Forking (#{i})"

body "Some content"

end

end

end

threads.map(&:join)

}

Этот код теперь дает следующие результаты (опять же, на четырехъядерном процессоре с MRI Ruby 2.0.0p353):

13.710000 0.040000 13.750000 ( 13.740204)

Bummer. That sure isn’t very impressive! So what’s going on? Why is this producing almost the same results as we got when we ran the code synchronously?

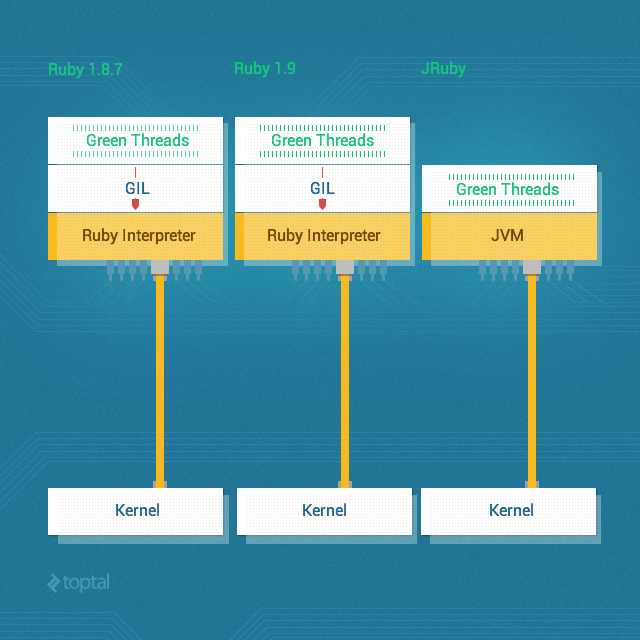

The answer, which is the bane of existence of many a Ruby programmer, is the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). Thanks to the GIL, CRuby (the MRI implementation) doesn’t really support threading.

The Global Interpreter Lock is a mechanism used in computer language interpreters to synchronize the execution of threads so that only one thread can execute at a time. An interpreter which uses GIL will always allow exactly one thread and one thread only to execute at a time, even if run on a multi-core processor. Ruby MRI and CPython are two of the most common examples of popular interpreters that have a GIL.

So back to our problem, how can we exploit multithreading in Ruby to improve performance in light of the GIL?

Well, in CRuby, the unfortunate answer is that you’re basically stuck and there’s very little that multithreading can do for you.

But if you have the option of using a version other than CRuby, you can use an alternative Ruby implementation such as JRuby or Rubinius, since they don’t have a GIL and they do support real parallel threading.

To prove the point, here are the results we get when we run the exact same threaded version of the code as before, but this time run it on JRuby (instead of CRuby):

43.240000 0.140000 43.380000 ( 5.655000)

Now we’re talkin’!

But…

Threads Ain’t Free

The improved performance with multiple threads might lead one to believe that we can just keep adding more threads – basically infinitely – to keep making our code run faster and faster. That would indeed be nice if it were true, but the reality is that threads are not free and so, sooner or later, you will run out of resources.

Let’s say, for example, that we want to run our sample mailer not 100 times, but 10,000 times. Let’s see what happens:

threads = []

puts Benchmark.measure{

10_000.times do |i|

threads << Thread.new do

Mailer.deliver do

from "eki_#{i}@eqbalq.com"

to "jill_#{i}@example.com"

subject "Threading and Forking (#{i})"

body "Some content"

end

end

end

threads.map(&:join)

}

Boom! I got an error with my OS X 10.8 after spawning around 2,000 threads:

can't create Thread: Resource temporarily unavailable (ThreadError)

As expected, sooner or later we start thrashing or run out of resources entirely. So the scalability of this approach is clearly limited.

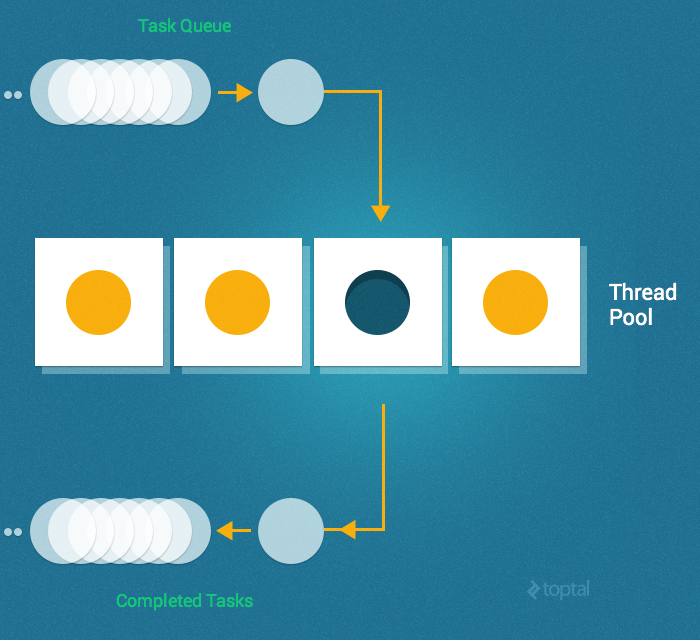

Thread Pooling

Fortunately, there is a better way; namely, thread pooling.

A thread pool is a group of pre-instantiated, reusable threads that are available to perform work as needed. Thread pools are particularly useful when there are a large number of short tasks to be performed rather than a small number of longer tasks. This prevents having to incur the overhead of creating a thread a large number of times.

A key configuration parameter for a thread pool is typically the number of threads in the pool. These threads can either be instantiated all at once (i.e., when the pool is created) or lazily (i.e., as needed until the maximum number of threads in the pool has been created).

When the pool is handed a task to perform, it assigns the task to one of the currently idle threads. If no threads are idle (and the maximum number of threads have already been created) it waits for a thread to complete its work and become idle and then assigns the task to that thread.

So, returning to our example, we’ll start by using Queue (since it’s a thread safe data type) and employ a simple implementation of the thread pool:

require “./lib/mailer” require “benchmark” require ‘thread’

POOL_SIZE = 10

jobs = Queue.new

10_0000.times{|i| jobs.push i}

workers = (POOL_SIZE).times.map do

Thread.new do

begin

while x = jobs.pop(true)

Mailer.deliver do

from "eki_#{x}@eqbalq.com"

to "jill_#{x}@example.com"

subject "Threading and Forking (#{x})"

body "Some content"

end

end

rescue ThreadError

end

end

end

workers.map(&:join)

In the above code, we started by creating a jobs queue for the jobs that need to be performed. We used Queue for this purpose since it’s thread-safe (so if multiple threads access it at the same time, it will maintain consistency) which avoids the need for a more complicated implementation requiring the use of a mutex.

We then pushed the IDs of the mailers to the job queue and created our pool of 10 worker threads.

Within each worker thread, we pop items from the jobs queue.

Thus, the life-cycle of a worker thread is to continuously wait for tasks to be put into the job Queue and execute them.

So the good news is that this works and scales without any problems. Unfortunately, though, this is fairly complicated even for our simple example case.

Celluloid

Thanks to the Ruby Gem ecosystem, much of the complexity of multithreading is neatly encapsulated in a number of easy-to-use Ruby Gems out-of-the-box.

A great example is Celluloid, one of my favorite ruby gems. Celluloid framework is a simple and clean way to implement actor-based concurrent systems in Ruby. Celluloid enables people to build concurrent programs out of concurrent objects just as easily as they build sequential programs out of sequential objects.

In the context of our discussion in this post, I’m specifically focusing on the Pools feature, but do yourself a favor and check it out in more detail. Using Celluloid you’ll be able to build multithreaded programs without worrying about nasty problems like deadlocks, and you’ll find it trivial to use other more sophisticated features like Futures and Promises.

Here’s how simple a multithreaded version of our mailer program is using Celluloid:

require "./lib/mailer"

require "benchmark"

require "celluloid"

class MailWorker

include Celluloid

def send_email(id)

Mailer.deliver do

from "eki_#{id}@eqbalq.com"

to "jill_#{id}@example.com"

subject "Threading and Forking (#{id})"

body "Some content"

end

end

end

mailer_pool = MailWorker.pool(size: 10)

10_000.times do |i|

mailer_pool.async.send_email(i)

end

Clean, easy, scalable, and robust. What more can you ask for?

Background Jobs

Of course, another potentially viable alternative, depending on your operational requirements and constraints would be to employ background jobs. A number of Ruby Gems exist to support background processing (i.e., saving jobs in a queue and processing them later without blocking the current thread). Notable examples include Sidekiq, Resque, Delayed Job, and Beanstalkd.

For this post, I’ll use Sidekiq and Redis (an open source key-value cache and store).

First, let’s install Redis and run it locally:

brew install redis redis-server /usr/local/etc/redis.conf

With out local Redis instance running, let’s take a look at a version of our sample mailer program (mail_worker.rb) using Sidekiq:

require_relative "../lib/mailer"

require "sidekiq"

class MailWorker

include Sidekiq::Worker

def perform(id)

Mailer.deliver do

from "eki_#{id}@eqbalq.com"

to "jill_#{id}@example.com"

subject "Threading and Forking (#{id})"

body "Some content"

end

end

end

We can trigger Sidekiq with the mail_worker.rb file:

sidekiq -r ./mail_worker.rb

And then from IRB:

⇒ irb

>> require_relative "mail_worker"

=> true

>> 100.times{|i| MailWorker.perform_async(i)}

2014-12-20T02:42:30Z 46549 TID-ouh10w8gw INFO: Sidekiq client with redis options {}

=> 100

Awesomely simple. And it can scale easily by just changing the number of workers.

Another option is to use Sucker Punch, one of my favorite asynchronous RoR processing libraries. The implementation using Sucker Punch will be very similar. We’ll just need to include SuckerPunch::Job rather than Sidekiq::Worker, and MailWorker.new.async.perform() rather MailWorker.perform_async().

Conclusion

High concurrency is not only achievable in Ruby, but is also simpler than you might think.

One viable approach is simply to fork a running process to multiply its processing power. Another technique is to take advantage of multithreading. Although threads are lighter than processes, requiring less overhead, you can still run out of resources if you start too many threads concurrently. At some point, you may find it necessary to use a thread pool. Fortunately, many of the complexities of multithreading are made easier by leveraging any of a number of available gems, such as Celluloid and its Actor model.

Another way to handle time consuming processes is by using background processing. There are many libraries and services that allow you to implement background jobs in your applications. Some popular tools include database-backed job frameworks and message queues.

Forking, threading, and background processing are all viable alternatives. The decision as to which one to use depends on the nature of your application, your operational environment, and requirements. Hopefully this article has provided a useful introduction to the options available.